Church member Linda Tarnay, center, cuts the ribbon of the new ramp as her caregiver, the Rev. Winnie Varghese and the Rev. Anne Sawyer watch. The Dec. 2 ramp blessing ceremony celebrated a challenging five-year project to make the historic New York’s St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery more accessible to people with mobility disabilities. Photo: Amy Sowder/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] Linda Tarnay used to leap across the hardwood floors in the nave of St. Mark’s Church in-The-Bowery in Manhattan’s East Village.

A member of the historic Episcopal church for more than 25 years, she also taught dance at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts for 35 years, owned a dance company and earned many accolades. These days, even crossing the threshold of her church is a challenge since her Parkinson’s diagnosis. Tarnay uses a wheelchair to get around, and St. Mark’s is a historical landmark building, which like many old church buildings was not built with access for those with disabilities.

“I try to come as much as I can,” Tarnay said recently at a church reception, as her caregiver brought her a bite to eat.

As the Episcopal Church’s worshippers age along with its buildings, needs rise for more disability accommodations. Plus, the welcoming, inclusive vibe churches strive for can be made more tangible with accommodations for people of all abilities, regardless of age.

Money for building-access renovations or technology for the hearing or vision impaired is often not in congregational or diocesan budgets, say advocates who’ve sought funds. And building maintenance often gets priority.

Because grant money is severely limited, projects such as ramps and lifts for handicap accessibility aren’t always eligible for grants, but in the Diocese of New York they are eligible for loans on a case-by-case basis, said Michael Rebic, director of the diocese’s property support committee.

There can also be less motivation to do these renovations because churches are often exempt from federal accessibility requirements.

But for the Rev. Winnie Varghese, the temporary, rickety wooden ramp that Tarnay had to use was unacceptable. She wanted St. Mark’s to practice what she calls “radical welcome.” As interim rector at St. Mark’s, she pushed hard to get a ramp installed at the front entrance. Today, Varghese is the director of justice and reconciliation at Trinity Church Wall Street in lower Manhattan, about 2.5 miles south of St. Mark’s.

“This church learned that it has many more values besides this historic site and this building: the people in this place, the mission that has been developed here together over the years, its fine commitment to the arts, to social justice, to radical inclusion,” Varghese told the crowd at a Dec. 2 Blessing of the Ramp ceremony.

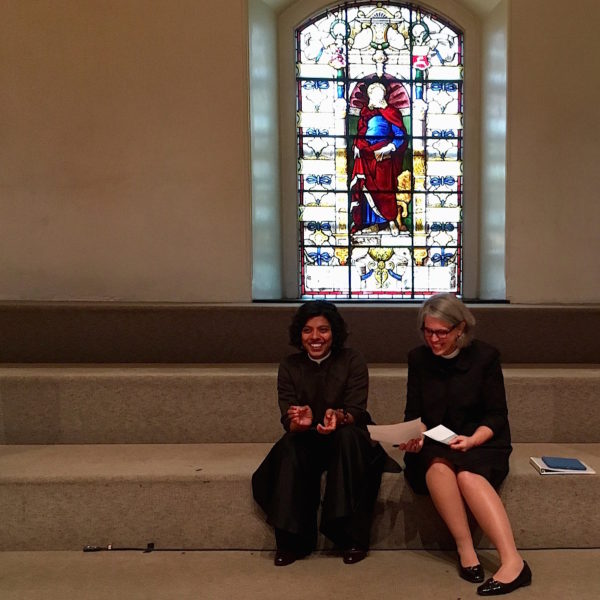

The Revs. Winnie Varghese and Anne Sawyer sing along to the St. Mark’s ramp blessing song, adapted from the “This Land Is Your Land” song by Woody Guthrie. Photo: Amy Sowder/Episcopal News Service

“And actually, this place … has found a way to preach its values through its site,” she said. The ramp is now a visual symbol of the church’s mission to be radically welcoming and inclusive, she added.

Historic Preservation

Many Episcopal churches are more than a century old. When maintaining the buildings, some conflicting values can butt heads: preserving the original historical structure and ensuring everyone — regardless of ability — can enter the building.

That contention was especially true for St. Mark’s, which had members of the church and community opposed to adding an access ramp in front of the prominent landmark.

With the property’s roots as a church starting in 1651 and Episcopal ownership in 1793, St. Mark’s is the oldest place of continuous Christian worship in New York, according to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Walter B. Melvin Architects was the preservation architect for the portico restoration and access ramp installation, which took five years to complete from design to construction. Much of this time was devoted to integrating the design with the historic site, obtaining the permits and approvals required from several city agencies and the community board, as well as an extended fundraising campaign to accomplish the whole project.

“Finally done,” said David van Erk, project manager. “I’m glad they were able to achieve their goal. Their persistence helped them through the obstacles they ran into with obtaining permits and financing. All in all, a successful project, and it fits in with its surroundings.”

More than a month after the ramp concrete dried, Tarnay said the new ramp makes it easier for her to attend church.

“There’s a more welcome feeling when I am there,” she said.

Linda Tarnay, left, pushed by her caregiver, proceeds up the access ramp at the Blessing of the Ramp ceremony at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery in New York. Photo: Amy Sowder/Episcopal News Service

Founded more than 300 years ago, Trinity Church Wall Street is also exploring a renovation that includes installing wheelchair-accessible ramps around the building’s perimeter, said Nathan Brockman, communications and marketing director.

In Newark, New Jersey, the House of Prayer Episcopal Church still lacks easy access from the church to the parish hall, said the Rev. Joyce Bearden McGirr, the priest-in-residence. Built before 1725, the site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

“To get to the parish hall from the sanctuary requires climbing steep stairs, which is difficult for both congregations worshipping there,” McGirr said. “Also, the entrance to the parish hall from the street requires climbing stairs.”

The priest said she isn’t aware of past accessibility discussions, but she’d like improvements.

Before the Rt. Rev. Jennifer Baskerville-Burrows became the bishop of the Diocese of Indianapolis, she worked as a religious property preservation consultant for 10 years, among other roles. She studied architecture and earned a master’s degree in historic preservation, completing her thesis on how churches and preservation communities can work together.

The state of Indiana, as well as New York, have sacred places programs, which can assist with fundraising, Baskerville-Burrows said. United Thank Offering grants can sometimes help fund accessibility projects too, when the request is tied to a mission.

Still, the cost of maintaining old churches can be insurmountable, not to mention the spiritual and social cost to those who can’t participate in church activities because of lack of access.

One of the last parishes where Baskerville-Burrows served was on the National Registry of Historic Places. She has watched so much money goes to minimal upkeep of buildings like these, at the sacrifice of the mission of the churches.

“As much as I love historic buildings and have worked decades to keep them upright, I think sometimes there are better caretakers of them, and it’s best to let them go,” she said. “We’re not about our buildings. We’re about our people, our faith and our ministry. It’s about reconciling people and being reconciled to God.”

“Those are some hard choices in terms of other losses in our church these days,” Baskerville-Burrows said.

Complying with the Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in all areas of public life.

That includes jobs, schools, transportation and all public and private places that are open to the general public. But the ADA exempts religious organizations and entities controlled by religious organizations, so in many cases, churches don’t have to be accessible. Access can mean many things.

With roots in the 1849 Gold Rush, Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, seat of the Diocese of California, today has elevators and three wheelchair-accessible ramps. At Sunday services, the liturgy and order of worship are printed out for the hard of hearing.

That helps Karma Quick-Panwala. She’s a special-education advocate for families of children with disabilities, and she’s also severely hard-of-hearing. Trained as a child in lip-reading, Quick-Panwala is not fluent in sign language.

Since 2011, she’s used Community Access Realtime Translation services, or CART services, at the annual Diocese of California conventions.

“But the benefits of real-time captioning could help everybody, not just me, and it could help record-keepers and provide transcriptions,” Quick-Panwala said.

All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Pontiac, Michigan, began as a parish called Zion Episcopal Church in 1837 and its current building was completed in 1950, according to the website’s historical timeline. Between 2000 and 2007, the church became a universally accessible building with ramp access to the sanctuary and parish hall, elevator access to all floors and front pews with space for wheelchairs.

Former House of Deputies President Bonnie Anderson attends All Saints’ along with her husband and their adult son who uses a wheelchair.

“For me, at least with a son that needs accessibility, it’s all about the baptismal covenant. We promise, with God’s help, to respect every person’s dignity,” Anderson said. “As churches, I think we have a responsibility to people who need extra help. We have ‘The Episcopal Church Welcomes You’ on our signs. Everyone is welcome. We say that, don’t we?”

Providing equal mobility access goes beyond the entrances.

When an older church has difficult chancel steps and doesn’t have an accessible altar, sometimes communion is brought to people sitting in the pews who need help. “Some people don’t mind that, and other people don’t like it at all. It singles you out from the congregation and makes your disability more visible,” Anderson said.

Some people would prefer to take communion at a standing station at the bottom of those chancel steps, where the priest and lay eucharistic minister stand, she said. The church bulletin can spell out the options.

Churches that have parish schools are legally required by the ADA to be accessible, said the Rev. Paul Feuerstein, a multi-vocational priest who assists at St. Mark’s in-the-Bowery and is president and chief executive officer of Barrier Free Living. The multi-service agency helps disabled victims and survivors of domestic violence and homelessness.

Because there are resident arts organizations at St. Mark’s, there are often public poetry and dance events onsite, so the church is legally required to make reasonable accommodations, Feuerstein said.

“But it really came out of a passion for social justice and to make a statement of radical welcome,” he said of the ramp project. “I would hope other churches do it, not because they have to, but because they want to.”

Feuerstein was a founding member of an access committee in the Diocese of New York, but the committee hasn’t been active in several years. He’s done disability work since 1978.

Whatever the legal requirements are for a particular church building, event or activity, it’s really about parishes taking up that mantle, Feuerstein said.

Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, California, offers accessibility for people with mobility, hearing and sight disabilities. Photo courtesy of Bobak Ha’Eri

“All too often, people who end up with disabilities, aging people, don’t like to use the ‘d’ word. I get it. There’s a reminder of vulnerability that impacts people’s embracing the issue.”

Resolving to change on a larger scale

Quick-Panwala’s request for CART services at the 78th General Convention in 2015 was received shortly before the start of the 78th General Convention and was unable to be accommodated with the limited time and resources available, according to Lori Ionnitiu, director of meetings and convention in the church’s Office of the General Convention.

Because Quick-Panwala can’t read sign language, the Diocese of California helped with funding remote captioning over Skype on her laptop. It’s not her preferred method because internet service is restricted and spotty, and it requires using a microphone. But she made it work.

CART services will not be available when the General Convention meets in Austin this July because there are no funds to provide complete services in English and Spanish in both houses, worship, all legislative committee meeting rooms, and the meeting of the Episcopal Church Women. Analysis by the Office of General Convention estimates the equipment and staff costs to be close to a half of a million dollars.

Quick-Panwala’s frustration with getting accommodations to participate in church activities inspired her to write a General Convention resolution encouraging the church to renew its commitment to provide full and equal access for all people with disabilities to any church program or activity. The 2015 resolution was sponsored by the Rev. Eric Metoyer, and it passed.

“Our church tends to have an aging population, and disability is almost a normal part of the aging process,” Quick-Panwala said. “Many people already have vision, hearing and mobility challenges. We want everybody to be able participate in church activities just the same.”

Although the resolution recommended that the Joint Standing Committee on Program, Budget and Finance budget $80,000 in the 2016-2018 triennium to fulfill accommodation requests at the 79th General Convention and at ancillary meetings and events, no money was allocated in the budget that PB&F presented and convention passed.

“It appears that there was little more done on the resolution than the formality of the church saying ‘Yes, we will provide more accessibility.’ That’s one reason why I pushed so hard for money to be attached,” Quick-Panwala said. “Somehow, there wasn’t any money in the Episcopal Church budget to allocate to it.”

It’s unfortunate, Quick-Panwala said, that General Convention resolutions often ask for money to be allocated in the next three-year budget but PB&F cannot always fund all those requests.

The resolution also calls for the General Convention Office to work with the Episcopal Disability Network and the Episcopal Conference of the Deaf to develop a set of best practices for providing disability accommodations at all official and ancillary church events. Such guidelines would help dioceses and churches when someone asks for a disability accommodation, Quick-Panwala said.

The Rev. Michael Barlowe, the secretary of General Convention, told ENS the Executive Office of General Convention continues to work with the Conference of the Deaf to provide and coordinate interpreters for the deaf at General Convention and also offer enhanced listening devices for those that are hard of hearing.

“It is important for us to work closely with those organizations specifically connected to the deaf, hard of hearing and related communities to consider best practices for all attending General Convention and other meetings of the Episcopal Church,” Barlowe said. “These historic connections go back over a century, and the differing opinions about best practices within these communities is ongoing.”

Besides following Jesus’ example, providing more accommodations for people with disabilities can be a self-interested cause, Feuerstein said.

“Chances are, we’re going to end up there ourselves,” said Feuerstein, 70. “And the older we get, the more limitations we may end up with.”

— Amy Sowder is a special correspondent for the Episcopal News Service and a freelance writer and editor based in Brooklyn. She can be reached at amysowderepiscopalnews@gmail.com.

This post appeared here first: How Episcopal churches embrace ‘radical welcome’

[Episcopal News Service – General Convention 2015]